Abstract

Background: The most recent ONS data on Covid-19 showed Muslims to have the highest mortality risk of all groups in the UK, validating religion as an important, but frequently overlooked health determinant.

Amongst the Muslim population, gender inequalities result in Muslim women in particular being one of the

most vulnerable population groups, with several studies drawing attention to the substantially poor uptake and barriers of breast screening mammography amongst ethnic minority Muslim women. Importantly, more than 90% of Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in the UK are Muslim. Covid-19 has further amplified

populations and need addressing to reduce inequalities nationally.

Aim: This narrative review subsequently aims to summarize the barriers to mammography screening in Muslim women in the UK.

Methodology: A literature search was conducted on Medline and PubMed to identify relevant studies. A

strict inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in exclusion of any studies on mammography that did not have Muslim women in the population group. A thematic analysis of studies that met the final inclusion criteria was conducted and collated into a narrative review, organised by common barriers to mammography amongst Muslim women.

Results: 10 main themes were extracted, as follows: access to healthcare, fatalism, a preference for gender

concordant healthcare, perceived importance of mammography, lack of English language proficiency, modesty, family caring patterns, reliance on traditional healing practices, low income and finally a lack of trust in doctors.

Conclusion: This review provides critical insight into Muslim women’s intersectional experiences and the

unique role that religious belief systems and cultures may play in women’s engagement with breast cancer

screening. As well as highlighting deficits in the current breast screening programme in engaging and making the programme accessible to Muslim women. The review signposts a need to develop evidence based targeted interventions, that are culturally and religiously appropriate to overcome the perceived barriers for minority groups like Muslim women in the UK, with a view to reduce health disparities in the UK.

Background:

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer amongst women in the UK, with an incidence rate of 55,500 cases a year and a mortality rate of 11,500 deaths per annum(1). Women living in more deprived areas in the UK have an even higher risk of mortality(1)

These health inequalities are exacerbated by ethnic minority groups and shared religious beliefs collectively influencing their health beliefs and behaviours(2)

Muslims represent an ethnically diverse group with over 3 million in the UK, and close to half of them living in the most deprived areas(2).

The uptake of breast cancer screening services amongst groups living in deprived areas is poor and correlates with the rising rate of cancer among Muslims and ethnic minorities (2). Since more than 90% of Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in the UK are Muslim, this makes Muslims an especially high risk group, with recent ONS data on Covid-19 showing Muslims to have the highest mortality risk of all groups in the UK, demonstrating religion to be an important, but frequently overlooked health determinant (3). Amongst the Muslim population, gender inequalities result in Muslim women being one of the most vulnerable population groups, with several studies drawing attention to the substantially poor uptake and barriers of breast screening mammography amongst ethnic minority Muslim women. Few studies however have examined mammography barriers facing Muslim women in the UK, especially with Covid-19 having amplified these barriers(3). This narrative review subsequently aims to summarize the present day barriers to mammography screening in Muslim women in the UK.

Methods

Search Methods

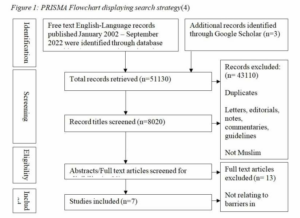

A literature search of free text English-Language, papers was conducted from January 2002 – September 2022 PubMed and MEDLINE databases were searched. Search terms included: ‘Muslim women’, ‘UK’, ‘barriers’, ‘mammography OR breast cancer screening’ as keywords (Figure 1). Initial database searches yielded 51,127 results on PUBMED and an additional seven on MedLine. Only review articles, systematic reviews, meta analysis, clinical trials and randomised controlled trials were included, all other study designs were excluded narrowing the search to 8020 results. Titles were screened for relevance and duplicates removed and 20 selected papers’ abstracts were reviewed. Four articles met the inclusion criteria with an additional three identified through a manual google scholar search. Seven papers were subsequently included in the review. This process is summarised in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis diagram (PRSIMA) (Figure 1)(4).

Study Design, Data extraction and Analysis

Selected studies were reviewed and data relevant to the aim of the study was extracted into an Excel Chart. Extracted data was analysed thematically and collated into a narrative review.

Results

Thematic analysis of studies identified 10 key themes.

Access to Healthcare

Socioeconomic constraints due to patriarchal family systems can hinder Muslim women’s access to mammography as they lack the autonomy and rely on male counterparts to make their medical decisions and to fund associated finances for example transport to facilitate these meetings, perpetuating delays in diagnosis(5).

Fatalism

The notion of events being predestined and by the will of God represents a generally accepted belief by Muslims, placing emphasis on prayers to endure their illness(5) While this can serve as a protective factor in some, the health belief that events are ‘out of one’s own control’ can also result in a corresponding reduction in some individuals’ motive to seek healthcare treatment and attend screening(5, 6).

Preference for gender concordant healthcare

A clear preference for female nurses and doctors among Muslim women in the UK is compounded across studies(2, 5-7). This is likely due to the intimate nature of the breast assessment which forms part of the breast screening programme, since exposure of intimate body parts to the opposite gender is not permitted in Islam. Muslim women’s preference of healthcare providers is described as a hierarchy in the bioethics of Islam as follows: 1) Muslim woman, 2) non-muslim woman, 3) muslim Man, 4) non-muslim man(6). However one study highlighted preferences for female physicians prevailed more in routine appointments such as breast cancer screening, compared with life-threatning situations where preservation of life became the key concern(7).

Perceived importance of mammography

Amongst British-South Asian Muslim women there is a perception that breast cancer screening is a symptom treating service, rather than a cancer detecting service for both asymptomatic and symptomatic women(7).

Mammography is therefore viewed by some muslim women as unimportant(7, 8). This is maybe due to the

conservative culture that prevails in south Asians and muslim groups, whereby certain topics like women’s health and cancer are not openly discussed, limiting the spread of knowledge within the community groups(5). A large sub-group of muslim women in the UK are immigrants that have come from developing countries, and therefore lack knowledge and awareness about the UK breast screening system that British women born and brought up in the UK may otherwise have been exposed to(5). Whilst amongst some muslim women religious beliefs pertaining to God controlling disease, can alter their health beliefs and behaviours and reduce their perception of self-risk from breast cancer(9).

Lack of English language proficiency

Poor English literacy among many muslim women, in particular among British Pakistani women constitutes a barrier to mammography(7).As communications regarding mammography appointments via post or email in English, containing medical terminology, may not be understood, or may require other family members to translate, and may delay attendance or result in important information being missed, as the communications are ignored or thrown away(7). Similarly, during mammography women not proficient in English may not comprehend information relayed to them by the radiographer or radiologist and may rely on taking family members as translators, resulting in additional obstacles to attendance(7). This is especially the case if there is a lack of understanding or perceived importance of breast cancer screening amongst other family members(7)

Modesty

Maintaining modest dress is fundamental in Islam and believing men and women are told to guard their private parts. This can pose a moral and religious dilemma when asked to expose their breasts for assessment, compounded by the fear and embarrassment that the examining physicians or technicians may be male(6,9) 10). Islamic modesty not only shapes the way Muslim women dress but also their speech, such that female body parts and related topics including breast cancer may not be subsequently spoken about openly, contributing to poor health literacy (5, 9).

Family caring patterns

Strong family caring patterns in muslim families can have both positive and negative outcomes on muslim women’s healthcare, and can result in some women putting the needs of their family, including household and care commitments, above their own, at the detriment of their health(2, 5, 6, 9). Meanwhile, efforts to attend mammography may be hampered by patriarchal family dynamics which prevail in some muslim families, in instances where the male head of the household may not permit the woman to attend the screening(5)

Reliance on traditional healing practices

Meetings with religious healers, fasting, prayer practices and consumption of foods like dates and black seeds constitute some of the traditional healing practices adopted by muslim women in the UK (2,5 6). Whilst these activities may be beneficial, they can diminish any motive to attend breast screening and seek help from healthcare professionals.

Low income

Muslim women from low socio-economic groups immigrants and refugee women living in deprived areas may by limited in their time due to the need to prioritise work and provide family income or may be reliant on family members for financial support to fund travel costs to attend the breast screening services(6). This can result in some muslim women wanting to attend mammography but not being able to due to circumstances(6)

Lack of trust in doctors

Experiences of religious and racial bias or discrimination faced by Muslim women, especially immigrant or refugee women that may have language barriers can negatively impact health seeking behaviours and perspective on doctors and hospitals in the UK Meanwhile, unfamiliarity with the UK healthcare system can impede trust in doctors, with muslim women occasionally only seeking medical care as a final resort(2).

Conclusion and recommendations

This review provides critical insight into Muslim women’s intersectional experiences and the unique role that religious belief systems and cultures play in women’s engagement with breast cancer screening. It highlights deficits in the current UK breast screening programme and signposts a need to develop evidence based targeted interventions, that are culturally and religiously appropriate to overcome the perceived barriers for minority groups like Muslim women in the UK, with a view to reduce health disparities in the UK.

Tables and Figures

Table 1: Containing the Keywords and associatedMESH

terms used on PUBMED.

References

- Cancer Research UK. Cancer Statistics for the

UK 2022 [updated 2022. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics - Christie-de Jong F, Kotzur M, Amiri R, Ling J,

Mooney JD, Robb KA. Qualitative evaluation of a

codesigned faith-based intervention for Muslim

women in Scotland to encourage uptake of breast,

colorectal and cervical cancer screening. BMJ Open.

2022;12(5):e058739. - Institue. PP. Challenging Health Inequalities.

2021. - PRISMA. PRISMA Flow Diagram 2020 [Available

from: https://www.prisma

statement.org//PRISMAStatement/FlowDiagram - Tackett S, Young JH, Putman S,Wiener C,

Deruggiero K, Bayram JD. Barriers to healthcare

among Muslim women: A narrative review of the

literature.Women’s Studies International Forum.2018;69:190-4 - Racine L, Isik Andsoy I. Barriers and Facilitators

Influencing Arab Muslim Immigrant and Refugee

Women’s Breast Cancer Screening: A Narrative

Review. J Transcult Nurs. 2022;33(4):542-9 - Woof VG, Ruane H, Ulph F, French DP, Qureshi

N, Khan N, et al. Engagement barriers and service

inequities in the NHS Breast Screening Programme:

Views from British-Pakistani women. Journal of

Medical Screening. 2020;27(3):130-7 - Woof VG, Ruane H, French DP, Ulph F, Qureshi

N, Khan N, et al. The introduction of risk stratified

screening into the NHS breast screening Programme: views from British-Pakistani women.

BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):452. - Padela AI, Malik S, Ally SA, Quinn M, Hall S,

Peek M. Reducing Muslim Mammography

Disparities: Outcomes From a Religiously Tailored

Mosque-Based Intervention. Health Educ Behav.

2018;45(6):1025-35. - Marlow LA, McGregor LM, Nazroo JY,Wardle J.

Facilitators and barriers to help-seeking for breast

and cervical cancer symptoms: a qualitative study

with an ethnically diverse sample in London.

Psychooncology. 2014;23(7):749-57.