Abstract

BACKGROUND: There is low uptake of primary care mental health services by minority faith groups in the UK and poorer health outcomes. Commonly perceived barriers to access include the fear of cultural naivety, insensitivity and discrimination suggesting NICE guidance on addressing cultural depression is not routinely implemented.

Faith-sensitive psychotherapy can be as effective or even more effective than standard approaches and is enthusiastically received by service users for whom religion is an important value. Researchers at the diversity in treatment for University of Leeds have developed a faith-sensitive therapy for Muslim clients (BA M) based on Behavioural Activation, an existing evidence-based treatment for depression. The BA-M model provides a useful starting point for exploring the treatment needs of a broader range of religious groups.

METHODS: An interfaith workshop hosted by Sharing Voices, a community mental health organisation in Bradford, and funded by the Bradford Clinical Commissioning Group facilitated small group discussions with participants from a range of religious groups and occupational backgrounds. Discussions focused on the extent of demand for faith sensitive approaches in the religious community to which participants belonged, approaches that would help develop faith-sensitive treatments and views on whether the BA-M resources could be adapted to different faiths groups.

RESULTS: There was strong support from participantsfor faith sensitive approaches in therapy. Feedback highlighted the importance of involving religious leaders and service users in development, accredited personnel and validated materials, safe spaces for therapy, interagency collaboration, cultural competence and person-centred approaches. There w s aclear consensus that the BA-M approach could be adapted to other faith groups to make mental health services more accessible and relevant.

CONCLUSION: The workshop provides evidence of a need to work with a broad range of religious communities to develop faith sensitive therapies for depression, to which access is currently limited in the UK.

Introduction

Mental health and minority religious groups

NICE guidelines highlight that it is essential for mental health practitioners to address clients’ ethnic and cultural identity when developing and implementing treatment plans (1). This guidance is supported by evidence that improving patient, practitioner and service understanding of therapy in the context of culture can improve cultural sensitivity in psychological therapy services (2,3)

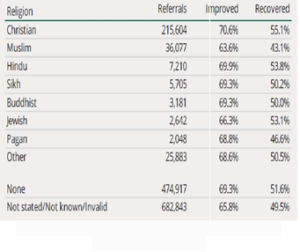

However, commonly perceived barriers to accessing mental health services for minority faith communities include the fear of cultural naivety, insensitivity and discrimination(4). There is evidence of disproportionately low uptake of IAPT services by those from minority faith groups in the UK s well as poorer outcomes (5). Between 2018-2019 information on religion was collected for around two-thirds of IAPT referrals; Figure 1 shows that those identifying as Christian or no religion were more likely to recover after IAPT treatment than other groups. In comparison, only 43% of Muslim clients, 47% of Pagan and 50% of Sikh and Buddhist clients moved to recovery(6).These low access and recovery rates in UK minority faith groups highlight a clear and urgent need for service development that takes account of their specific circumstances and needs (5).

Figure 1: IAPT referrals and outcomes by religion, 2020/21 (Baker 2021)

Figure 1: IAPT referrals and outcomes by religion, 2020/21 (Baker 2021)

Faith-sensitive therapy and mental health

Systematic reviews and meta analyses have shown the efficacy of culturally adapted therapies for depression and anxiety across a variety of religious and ethnic groups (7,8,9). Within this, a growing body of literature has highlighted the role of religion in supporting mental health and recovery and faith-adapted approaches have been associated with achieving positive treatment outcomes. Such therapies can involve the adaptation of secular protocols to take account of patients’ religious beliefs and values in order to be more client-cantered and sensitive to religion as a resource for health (10,11). Adaptations can also include specific training of therapists in cultural competence to enhance patient engagement and the use of culturally relevant metaphors to increase their relevance and meaning to clients (7, 8, 10).

This evidence shows that faith-sensitive psychotherapy protocols can be as effectiv or even more effective than standard approaches and is enthusiastically received by service users for whom religion is an important value. (10,12,13). Adapting existence evidence-based therapies to incorporate cultural elements has thus been widely recognized as an important step to increasing acceptability of these treatments, patient satisfaction and, ultimately, therapy effectiveness (10, 14,15,16,17).

BA for Muslim service users in Bradford

In recognition of the need for culturally-adapted therapies, researchers at the University of Leeds developed and piloted BA-M, an adapted therapy for Muslim clients, based on ehavioural Activation (BA), an existing evidence-based psychosocial treatment for depression(10). This adapted approach was based on an extensive literature review, that drew on a wide range of studies on diverse religious groups including Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish and Muslim populations (18). As part of the approach, a self-help booklet was developed in whichIslamic religious teachings that reinforced the therapeutic goals of BA were presented along with standard BA activity sheets. The booklet was offered to clients who identified religion as an important value in their life, following a Values Assessment (10).

Therapists and supervisors at a number of sites across England have been trained to deliver the culturally- adapted approach, which supports Muslim clients who choose to use ‘positive religious coping’ as a resource for health (5). A number of othe minority religious groups in the UK have expressed dissatisfaction with standard therapies and there is n increasing demand for approaches that incorporate spirituality into therapy (19). The need for cultural adaptation thus applies to a range of groups and the BA-M treatment model has potential to provide a useful starting p int on how to address their needs.

Methods

In order to gain an understanding of the need and demand for faith-based therapy across diverse religious groups in Bradford, an interfaith workshop was hosted by Sharing Voices, a community mental health organisation, and funded by the Bradford Clinical Commissioning Group. GM presented her research bout the BA-M model and, following this, small group discussions were facilitated with participants from a range of religious groups and occupational backgrounds (n=24).

Each group was asked to discuss and document their responses to the following three questions:

- Is there a need for faith sensitive approaches in the religious community to which you belong?

- What types of approaches would help?

- Could the BA-M self-help booklet be adapted to different faiths groups and if so how?

Participants self-selected their discussion groups and these were later classified into the following religion or professional categories to match representation at each table: Christian, Muslim, Hindu, police officers, voluntary or statutory sector mental health staff. Feedback from each group was discussed at the workshop by all participants and then collated for analysis into themes for each topic discussed (see Table 1)

Results

Need for faith sensitive treatment

There was strong support from all faith and professional groups for faith sensitive approaches in therapy. This was seen to provide a more holistic and person-centred treatment approach that supported greater respect and understanding of clients by therapists andwas likely to improve client trust. The approach was also considered helpful in terms of educating professionals and countering the negative views of faith beliefs that could exist in mental health services. As such,it had potential to facilitate better and deeper engage ent, particularly where clients and professionals had different explanations of the underlying health problem. The benefits of a more diverse workforce wereassociated with the need forsuch culturally sensitive approaches.

Drawing on faith and spirituality as a resource for mental healthwas considered an innovative ay ofsupporting positivity in therapy and diversifying treatment choices.

At the same time, participants recognised the need to ensure personal choice in terms of whether a focus on religion was supported, as well as inclusive approaches that were not limited to particular denominations. The importance of sensitivity as also noted in relation to possible feelings of guiltor fear of judgement that might deter people from engaging with therapy that linked to their religious beliefs.

Helpful approaches

In terms of how to develop faith-sensitive approaches, a number of groups and participants highlighted the importance of involving religious leaders in the creation and validation of therapy materials to ensure these were based on relevant values and social context. The accreditation of these materials and the personnel would deliver therapy was also emphasised, including a need for evidence-based and systemic approaches.

Feedback also focused on the importance of a safe space for therapy, which some groups identified as non-clinical and destigmatised settings such as places of worship or GP surgeries. Interagency collaboration, cultural competence and a person-centred approach were also identified as important aspects of delivery, with therapy in different languages, approachability of professionals and outreach to male clients highlighted as specific issues to be addressed.

Adaptability of BA-M to other religious groups

There was a clear consensus amongst participants that the existing BA-M self-help bookletc ould be adapted to other faith groups in order to make mental health services more accessible and relevant. The model was seen by participants in general as easily adaptable, with Christian and Hindu contributors endorsing the approach and highlighting the need to involve service users and religious scholars in adaptations to their particular faith communities.Again,the need for sensitivity to excluded subgroups within faith communities, such as LGBTQ people, who could fear being judged from a religious perspective was highlighted.

Conclusions and Next steps

The workshop provides evidence of a need for mental health services to work with a range of religious communities to develop appropriate faith-sensitive therapies to which access is currently limited in the UK. GM is collaborating with religious scholars from the Hindu community in Bradford, who are particularly interested in taking this work,to support positive religious coping within their communities.

References

- National Institute for Health and care Excellence (NICE) Depression in Adults: Recognition and Management.2009. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90[Accessed 03/12/2021]

- Bhui K, Bhugra D. Explanatory models for mental distress: implications for clinical practice and research. The British Journal of Psychiatry.2002 Jul;181(1):6-7.

- Tseng WS, Strelzer J, ed. Culture and psychopathology: A guide to clinical assessment.Routledge; 2013.

- Memon A, Taylor K, Mohebati LM, Sundin J, Cooper M, Scanlon T, de Visser R. Perceived barriers to accessing mental among black and minority health services ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open. 2016 e012337. AvailableNov 1;6(11):from: Adapted CognitiveBehavioral Therapy for religious individuals with mental disorder: a https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/11/e 012337.full.pdf [Accessed 03/12/2021)

- Mir G, Ghani R, Meer S, Hussain G. Delivering a culturally adapted therapy for Muslim clients with The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. 2019;12. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-cognitive-behaviour-therapist/article/delivering-a-culturally-adapted-therapy-for-muslim-clients- with- depression/B3457DB393BFD4C3B241AF32DBA2EE88 [Accessed 03/12/2021]

- Baker C. Mental health statistics for England: prevalence, services and funding. House of Commons Library 2021

- Anik E, West RM, Cardno AG, Mir G. Culturally adapted psychotherapies for depressed adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021 ;278:296-310.Available from : https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165032720327464 [Accessed 03/12/2021]

- Chowdhary N, Jotheeswaran AT, Nadkarni A, Hollon SD, King M, Jordans MJ, Rahman A, Verdeli H, Araya R, Patel V. The methods and outcomes of cultural adaptations of psychological treatments for depressive disorders: a systematic review. Psychological medicine. 2014 Apr;44(6):1131-46.

- Koenig HG, King,DE and Carson VB (2012) Handbook of Religion and Health. 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press

- Mir G, Meer S, Cottrell D, McMillan D, House A, Kanter JW. Adapted behavioural activation for the treatment of depression in Muslims. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015 Jul 15;180:190-9.

- de Abreu Costa M, Moreira-Almeida A. Religion-Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review and Description of Techniques. Journal of Religion and Health. 2021 Sep 13:1-24.

- Lim C, Sim K, Renjan V, Sam HF, Quah SL. Adapted CognitiveBehavioral Therapy for religious individuals with mental disorder: a systematic review. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014 Jun 1;9:3-12.

- Walpole, , McMillan, D., House, A., Cottrell, and Mir, G., 2013. Interventions for treating depression in Muslim Patients: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 145(1), pp.11-20.

- Bernal G, Scharrón-del-Río Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001 Nov;7(4):328.

- Sue In defense of cultural competency in psychotherapy and treatment. American Psychologist. 2003 Nov;58(11):964.

- Castro FG, Barrera Jr M, HolleranSteiker LK. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2010 Apr 27;6:213-39.

- Wright JM, Cottrell DJ, Mir G.Searching for religion and mental health studies required health, social science, and grey literature databases. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2014 Jul 1;67(7):800-10.

- Fernando S. Mental health, race and culture. Macmillan International Higher Education; 2010 Jan 29.

- Participants discussed copies of the booklet available at https://medicinehealth.leeds.ac.uk/dir-record/research-projects/980/addressing- depression-in-muslim-communities

Table 1: Interfaith workshop: small group discussion notes

| CHRISTIAN TABLE | MUSLIM TABLE | POLICE OFFICERS (SIKH, MUSLIM, CHRISTIAN,

NON-FAITH) |

TABLE OF VOL AND STATUTORY SECTOR PROFESSIONALS | HINDU TABLE | NOTES FROM WIDER GROUP |

|

Q1) Is there a need for faith sensitive approaches in the faith community to which you belong? |

|||||

| Yes

-The professional needs to align with faith as faith can provide guidance in the mental health sphere.

-It can provide diverse representation which is required among professionals.

-It can provide more positivity in therapy (messages of hope /love)

-Can help clients feel more understood |

Yes

-There is a massive demand for this type of support (faith sensitivity) in the Muslim community

-It can help clients feel more understood

-If a therapist is aware faith approaches it provides better understanding and shows respect which creates trust in that patient – therapist relationship. |

Yes, because it is person centred.

-It allows professionals to be mindful of culture versus religion.

-It is an alternative to medication.

-Can be used as an engagement tool This new and not something that has previously been adopted |

Yes

-It can be helpful to understand the importance of faith for a person.

-Learning about it would be helpful

-Professional curiosity

-Faith can sometimes be seen negatively in mental health services |

Yes

-There is definitely a need for a faith sensitive approach.

-discussion of faith is very important as it builds trust

-faith sensitive approach gives space for spiritual healing.

-It provides a more holistic approach e.g. If one cannot explain their symptoms and doctor can’t understand the problem, the problem will remain so a different approach like this will be helpful. |

-Yes there is a need for more diverse representation across the workforce generally.

-Professionals should have an overview of faith but don’t need specific details. -Some people might not be practicing. -Be more mindful of culture and religion. -It can help people connect on a deeper level and help with well-being. -It can open up new avenues in therapy and diversify the offer -Yes, faith and spirituality – is a huge resource -People turn to faith in difficult times, it is helpful -Sometimes people have moved away from faith and it should not be forced on them. -A person’s faith can be personal and they might not wish to share. -There are many different denominations within faith. -This can deter engagement as there might be a fear of judgement for accepting help “am I sinning”? |

| Q2) What type of approaches would help? | |||||

| -Group therapy

-A well designed and accredited spiritual support guide for pastors

-Spiritual leaders should be involved in the creation of the approach

-Inter-agency working

-a person-centred approach

-informed approach |

-Using a values- based system

-primarily a cognitive behaviour therapy type approach |

-Firstly, recognising the person as an individual and being sensitive to their religion.

-Deliver this via a faith leader and/or personnel who is accredited to offer advice. This will help contextualise the approach. |

-Professionals should be aware of religious calendars and have a genuine interest.

-By providing culturally competent and sensitive approach training for professionals

-Use integrated working and systemic approaches |

-Provide reassurance and a safe space

-Deliver in a non- clinical setting

-Express confidentiality and offer in different languages

-Therapies offered in place of worship/GP surgeries for easy access and this can also help to de- stigmatise accessing mental health support.

-Therapists should be trained and competent. |

-Scholars/Faith leaders should be involved

faith -Accredited person of faith to a credit the approach(s)

-Start with values Easily adaptable methods that can be used for other faiths.

-Use a person-centred approach especially for each age group. E.g. Different terminology for different age groups.

-Professionals should be approachable, be able to provide reassurance and ensure the therapy session is a safe space.

-Provide clear and accessible resources

-More male-based events are needed to get insight into whether this will help them. |

|

Q3) Could the B-AM self-help booklet be adapted to different faith groups and if so how? |

|||||

| -Yes, it can be adapted. It can provide insight into the different Scriptures and how they approach wellbeing.

-It is helpful to work with different faiths

-Service user involvement should inform the views in this.

-Use the BA-M and it’s approaches to see how we can improve wellbeing for other groups too (BAME/Faith groups) make the service accessible |

-Yes

-It is easily adaptable to Christianity, etc (Monotheistic Religions)

-It depends mainly on the client’s choice and their readiness to adapt to the book. |

-Yes, some parts might be transferable. | Yes | -BA-M booklet can be adapted by religious scholars/teachers to ensure appropriateness and pick out good learning and techniques | -Yes, it can definitely be used as the model is easily adaptable, always start with values.

-There are excluded groups within religion – LGBTQ, for example fear of judgement.

-Not a one size fits all approach – it needs to be made personal by being more faith conscious |