Abstract

Heart failure affects an estimated 64.3 million people worldwide (1). Heart transplantation is a well-established treatment option and remains the gold standard therapy for patients suffering from end stage heart failure (2) although major technological advancements have resulted in favourable outcomes following implantation of durable left ventricular assist devices (LVAD)(3). Currently, around 4000 adults undergo heart transplantation annually (4). However, the demand for donor hearts far outweighs the supply for this precious resource. This leads to increased waiting list mortalities, which range from 10 to 20%. Muslims needs religious guidance to combat the negative views toward donation in part due to religious concerns particularly in the rapidly evolving practice of transplantation. I aim to share my views as a surgeon in the broad context of organ donation and a recapitulation of the impact of the Covid 10 pandemic.

Organ Donation

Transplantation is truly a lifesaving act, but it is not possible without the generosity and altruism of organ donors and their families and the hard work, coordination and determination of all the medical teams also involved in the process.

Organ donation laws vary across different countries in the United Kingdom. In England, Max and Keira’s Law – the Organ Donation (Deemed Consent) Act, considers all adults in England as having agreed to donate their own organs when they die unless they record a decision not to donate (known as ‘opting out’) or are in one of the excluded groups but people still have a choice whether or not to donate, families will still be consulted and people’s faith, beliefs and culture will be respected. Those excluded will be people under 18, those who lack the mental capacity to understand the new arrangements and take the necessary action; people who have lived in England for less than 12 months or who are not living here voluntarily and those who have nominated someone else to make the decision on their behalf. Organ donation will not go ahead if a potential donor tests positive for COVID-19 and finally, few people die in circumstances where organ donation is possible. The legislation for Wales is ‘deemed consent’. This means that if you haven’t registered an organ and tissue donation decision (opt in or opt out), you will be considered to have no objection to becoming a (Authorisation) (Scotland) donor. The Human Tissue Act 2019 provides for a ‘deemed authorisation’ or ‘opt out’ system of organs and tissue donation for transplantation. The opt out system will apply to most adults aged 16 and over who are resident in Scotland. Under the opt out system, if you die in circumstances where you could become a donor and have not recorded a donation decision, it may be assumed you are willing to donate your organs and tissue for transplantation. The family will always be asked about the latest views of the deceased on donation, to ensure it would not proceed if this was against their wishes. Only in Northern Ireland is the current legislation to opt into organ and tissue donation by joining the NHS Organ Donor Register and sharing the decision with family. It is also possible to nominate up to two representatives to make the decision for the donor. These could be family members, friends, or other people, such as faith leaders (5).A jurisprudential opinion on ‘deemed consent’ with respect to the Organ Donation Act 2019 was recently published in this Journal confirming juristic viewpoint, that abiding by from an Islamic this law is in concordance with the Shariah’s rulings, not least because the person can opt-out of it during their lifetime. When an individual declines to exercise this right (one that is in operation throughout their life), it becomes their presumed consent that their organs may be taken for the benefit of another after the former’s death(6).

The impact of the Covid 19 pandemic on organ donation and transplantation

The latest report of Donor and Transplant Activity (up to 31 March 2021), compared with the previous year showed (7):

- there was a 25% fall in the number of deceased donors to 1,180

- the number of donors after brain death fell by 19% to 766, while the number of donorsafter circulatory death fell by 35% to 414

- the number of living donors fell by 58% to 444, accounting for 27% of the total number of organ donors

- the total number of patients whose lives were potentially saved or improved by an organtransplant fell by 30% to 3,391

On the other hand, the total number of patients registered for a transplant has decreased slightly (by 2%): - 4,256 patients are waiting for a transplant at the end of March 2021, with a further5,307 temporarily suspended from transplant lists

- 474 patients died while on the active list waiting for their transplant compared with 377 in theprevious year, an increase of 26%.

- A further 693 were removed from the transplant list. The removals were mostly because of deteriorating health and ineligibility for transplant and many of these patients would have died shortly.

Some of the other key messages from this report are that, compared with last year show:

- a fall of 33% in the total number of kidney transplants

- a fall of 49% in the total number of transplants involving a pancreas

- a fall of 19% in the total number of liver transplants

- a fall of 7% in the total number of heart transplants

- a fall of 44% in the total number of lung or heart-lung transplants

- a fall of 40% in the total number of intestinal transplants

Focus on Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities (members of non-white communities) in the UK

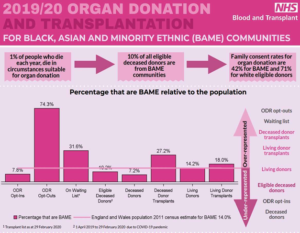

While there is an urgent shortage of organs for transplant for people from all backgrounds the problem is particularly acute for black, Asian, mixed race and minority ethnic patients. According to the Organ Donation and Transplantation data for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities Report for 2019/2020 (8), there is a high proportion of people from BAME backgrounds developing high blood pressure, diabetes and certain forms of hepatitis in the UK making them more likely to need a transplant at some point in their lives and they are indeed over-represented on the waiting list.

Getting the right tissue type and blood match is vital for the most successful transplant and the best match often comes from someone with the same ethnicity. In 2019/20,

Asian people represented 3% of total deceased donors, 14% of transplants from deceased donors and 18% of the transplant waiting list; while black people represented 2% of deceased donors, 9% of transplants from deceased donors and 10% of the transplant waiting list (figure 1).This shows the continued imbalance between the need for transplants in black and Asian communities and the availability of suitable organs with the right blood and tissue type. Currently, only around half as many families from these communities’ support donation compared to families from a white background, the numbers of BAME people becoming more engaged and agreeing to organ donation needs to be addressed. In 2015/16,5.8% of people from BAME communities who registered their ethnicity opted-in to the NHS Organ Donor Register and in2019/20 that rose to 7.8% although the report does not provide specific religion-centred data. There is significant over-representation in the number of opt-outs from BAME communities. Inparticular, 52% of these opt-outs were made by Asian people, mostly of Pakistani origin (30%),followed by white people (26%) and black people (17%).

Figure 1: Organ donation and transplantation in Black, Asian and ethnic minority (BAME) communities. Families are less likely to discuss organ donation and are much more likely to decline to donate organs for lifesaving transplants.

A recent survey in attitudes towards organ donation among black and Asian communities reveals a shift from a negative to a neutral position, this figure has almost halved over the last year while the proportion of people unsure whether they want to be a donor has grown, indicating and the number of black and Asian people who would donate some or all organs after their death has risen from 11 to 15 %.Almost double the number were aware that organs matched by ethnicity had the best chance of success. And three times as many people knew that those from black and Asian backgrounds are more likely to need an organ transplant than white people, table1 (9).

Not knowing what their relative wanted or believing that organ donation goes against their religious beliefs or culture are the main reasons given by BAME families for saying no to donation when approached by specialist nurses, meaning opportunities for lifesaving transplants are still being missed because families are reluctant to discuss the topic of organ donation.

Table 1: Results of survey in attitudes towards organ donation among BAME communities (initial benchmark survey was carried out by Agroni Research in May 2018 among 1,034 adults)

| May 2018 | March 2019 | |

| % of respondents who would not

donate their organs |

37 | 20 |

| % who didn’t know if they would

donate their organs |

30 | 43 |

| % correctly answered that a better a match is achieved with a donor of

same ethnicity |

22 |

39 |

| % of respondents stated that black

and Asian people are proportionally more likely to need an organ |

11 |

35 |

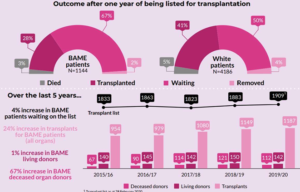

The number of BAME transplant recipients has increased year on year, while the number of BAME patients on the transplant list has grown at a smaller rate over this time. Each year there are consistently more BAME living donors than BAME deceased donors.

In 2019/20, there were 1187 deceased and living donor transplants for BAME patients, 142 living BAME donors, 112 deceased BAME donors whilst 1909 BAME patients were waiting for a transplant. Although in the last year, there was an increase in transplants for BAME recipients, it is likely that the suspension of elective surgeries as a result to COVID-19 had some impact on these figures. Last year, BAME patients accounted for a third of patients on the transplant waiting list, a quarter of all transplants and 10% of donors were from BAME communities, figure 2.

Figure 2: BAME patients’evolution on the transplant waiting list and 1 year outcome compared to White patients in the UK over the last 5 years.

The British Islamic Medical Association (BIMA) organised a national campaign on organ donation focussing on British Muslim attitudes towards organ donation. Of a total of 554 only 45 (8.1%) respondents were already registered donors. Reasons for not registering (n=127) were classified as faith beliefs & views on religious permissibility (73%), lack of knowledge on organ donation (21%), family influence & reluctance to discuss donation (2%), death & burial concerns (2%) and moral considerations (2%). Respondents from BAME backgrounds (Pakistani, Indian, Arab, Bangladeshi) were significantly less likely to be registered as organ donors than their White counterparts (p<0.001).Interestingly, the accompanying educational campaign demonstrated consistent net increase in the number of attendees considering organ donation to be religiously permissible, across all variables (10).

View from an Islamic perspective

The Prophet Mohammad (peace and blessings of Allah upon him said: )ص ﱠلى ٱ ﱣÆُ علَ ْي ِه وسلﱠ َم, “if one relieves a Muslim of his troubles, Allah will relieve his troubles on the day of resurrection”.

The scholars unanimously agreed that donating organs is regarded as an ongoing charity, and that the donor is rewarded with the permission of Allah. The Messenger of Allah (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) said: “When a son of Adam dies, his deeds cease apart from three: a righteous child who will pray for him, knowledge from which others may benefit after him, or ongoing charity”.

The body is impermanent and that helping our brethren with end stage organ failure is noble humanitarian work. They are more deserving of the organs of our dead than the dust, and Allah (SWT) says in the Holy Quran (if anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of all mankind). This is true of organ donation after brain death because it can improve quality of life for patients with organ failure.

The details of Islamic jurisprudence on organ donation transplantation are beyond the scope of this paper and the abilities of the author. However, I wish to add my personal comments to an exhaustive document and fatwa “Organ Donation and Transplantation in Islam”: An opinion produced in June 2019 by a UK-based scholar, Mufti Mohammed Zubair Butt, a Jurisconsult from the Institute of Islamic Jurisprudence (11).

Practice of Organ Retrieval in light of 2000, Fatwa of European Council for Fatwa and Research

In 2000, the European Council for Fatwa and Research (ECFR) declared its ratification of the resolutions of both the Islamic Fiqh Academy of the Muslim World League and the International Islamic Fiqh Academy on “Organ transplant from the body (dead or alive) of a human being on to the body of another human being” permitted with conditions. In relation to Deceased transplantation the resolution noted that death comprised two situations:

- Death of the brain with the complete cessation of all of its functions in which, medically, there is no reversibility.

- Complete cessation of cardiorespiratory functions in which, medically, there is no reversibility. In the first situation, two requirements needed to be met: firstly, the complete cessation of all brain functions [and not just of the brain stem] and, secondly, medical irreversibility [and not simply permanence]. The second situation also had two requirements: firstly, the complete cessation of cardiorespiratory functions and, secondly, medical irreversibility [and not simply permanence] (12).

In the UK, Donation after Brainstem Death (DBD) requires confirmation of death using neurological criteria (also known as brain-stem death or brain death)where brain injury is suspected to have caused irreversible loss of the capacity for consciousness and irreversible loss of the capacity for respiration. It follows the current UK Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Confirmation of Death published by the Academy of the Medical Royal Colleges in 2008 (13). This is compatible with the Islamic definition of death and is not contested by scholars nor Muslims in general.

Human dignity

Human dignity in Islam is recognised for all humans as an expression of God’s favour and grace. It is the absolute natural right of every individual regardless of gender, colour, race or faith, and is established from the explicit, alluded and inferred meanings of the evidentiary texts.

The UK National Organ Retrieval Services (NORS) teams deliver a high-quality service working in the same settings (sterile operating room) and with the same modus operandi as any surgical procedure on a living human being; indeed, it is not possible to differentiate from the outside this procedure from other complex surgical interventions. From start to finish the procedure is carried out with the utmost respect for the donor and in accordance with the family’s wishes. The procedure consists firstly in assessing the suitability of the organs and excluding the presence of major contraindications to donation that could pose a risk to the potential recipients. Retrieving the organs requires a highly skilled lead surgeon who is competent, accredited and capable of identifying and respecting the complexity of the donor’s anatomy. All lead surgeons are competent in dissecting the most delicate structures of the human body, preserving the relevant anatomy and ensuring a safe and successful transplantation. Organs that are not intended to be transplanted are NOT retrieved unless specified and agreed at time of consent authorisation. Organs are then safely packed into boxes that keep them cool while in transit to the transplant centre. On arrival, the transplant surgeon will again check the quality of the organs before proceeding to the transplant operation. The retrieval operation is concluded with the team de-briefing.

Conclusion

Deceased Organ Donation and Transplantation in the UK aligns with Islamic practice in meeting all requirements to indicate the departure of the soul from the body, and in the absence of any clear evidence to prohibit the transplantation of human organs and in the pursuit of public interest, it is permissible and is provided with the assurances that the organ or tissue is donated with the willing consent, whether express or implied, of the deceased and the procedure is conducted with the same dignity as any other surgery.

British Muslims are less likely than British non-Muslims to be organ donors, and religious concerns are a major, but not the only, perceived barrier. Further education may improve organ donation rates among the Muslim community as there is need more people from BAME and Muslim communities to be prepared to donate in life or after death.

References

- Groenewegen A, Rutten FH, Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Epidemiology of heart Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(8):1342-56.

- Savarese G, Lund LH. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Card Fail Rev. 2017;3(1):7-11.

- Miller L, Birks E, Guglin M, Lamba H, Frazier OH. Use of Ventricular Assist Devices and Heart Transplantation for Advanced Heart Failure. Circulation Research. 2019;124(11):1658-78.

- Lund LH, Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb S, Kucheryavaya AY, Levvey BJ, et The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fourth Adult Heart Transplantation Report 2017: Focus Theme: Allograft ischemic time. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2017;36(10):1037-46.

- https://organdonation.nhs.uk/helping-you-to- decide/organ-donation-laws/

- Al-Judai A jurisprudential opinion on ‘deemed consent’ with respect to the Organ Donation Act 2019 Aug 26, 2020. www.bima.com

- https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco- assets-corp/23466/section-1-summary-of-donor- and-transplant-activity.pdf

- https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/supporting-my- decision/statistics-about-organ-donation/transplant-activity-report/#bame

- https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/news/survey-reveals- shift-in-attitudes-towards-organ-donation-among-black-and-asian-communities/

- Ali O, Gkekas R, Tang T, Ahmed S, Ahmed S, Chowdhury I, Al-Ghazal S. “Let’s Talk about Organ Donation”; from a UK Muslim Perspective. Aug 26, 2020. www.bima.com

- https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco- assets-corp/16300/organ-donation-fatwa.pdf

- Ghaly Religio-ethical discussions on organ donation among Muslims in Europe: an example of transnational Islamic bioethics. Med Health Care and Philos (2012) 15:207–220. DOI 10.1007/s11019-011-9352-x

- Wijdicks EF, Varelas PN, Gronseth GS, Greer DM. Evidence-based guideline update: determining brain death in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010 Jun 8;74(23):1911-8