Abstract

This article discusses the social construct of khuntha from an Islamic perspective. Assignment of sex at birth and monitoring gender identity beyond puberty is also examined through the lens of Islamic jurisprudence. Gender-affirming surgery (GAS) is investigated in light of ground-breaking fatwas in recent decades that permit the procedure. The main arguments underlying the view of permissibility include the personal need to address gender dysphoria, the personal desire to correct one’s physical attributes, and the absence of explicit prohibition in Shariah law. Because the surgical operation is irreversible with lifelong consequences, several ethical issues are highlighted that need to be considered collectively by a panel which needs to include the intersex person, their loved ones, gender psychologists, surgeons, and the fuqaha.

Introduction

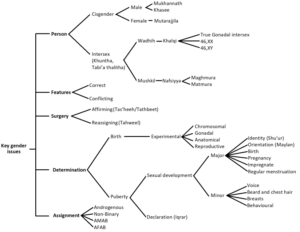

Intersex persons have been acknowledged in Shariah law as equals to persons who are cisgender. This acknowledgement includes mention of intersex persons in the books of tafseer, hadith, and fiqh, which are foregrounded in this article. However, due to the rarity of intersex persons in society (around 1.7% of the population)[1], most Muslims might never interact with an intersex person or ever realise that there are any in their communities. Research on intersex from an Islamic perspective is growing. For a list of fatwas related to intersex persons, read Zabidi for an analytical review of contemporary fatwas in resolving biomedical issues over gender ambiguity [2] and Malim and Padela wherein they review 23 online fatwas [3]. In this article, I hope to provide a fresh perspective on the matter of gender-affirming surgery (henceforth GAS) that involves collaboration between the intersex person, their loved ones, medical experts, and the fuqaha. I also point out key gender terminology that is used in fiqh in tandem with terms used in gender studies to empower the reader to have an interdisciplinary understanding of gender matters and to help make distinctions between aspects of gender to avoid conflating issues. In Table 1, I propose an intersex fiqh network which shows in tabular form the concepts discussed in this article and the way different aspects of gender matters relate to each other using current biomedical nomenclature.

Socially constructed terminology for sex and gender

In classical Islamic jurisprudence, ‘sex’ in the biological sense was realised by the noun ‘jince’ as in ‘jince al-rijal’and ‘jince al-nisa’ meaning the male and female sexes respectively. Gender identity, on the other hand, was referred to by the act of ‘iqrar’to mean an individual’s self-identification that was acquired from a strong sense of their gender; for instance, Imam Muhammad al-Shaybani (d. 805 CE) writes in his work al-Asl ‘aqarra annahu rajul’ and ‘aqarra annahu mar’a’meaning ‘one self-identifies as male’ or ‘female’ respectively[4]. Bearing in mind this sophisticated understanding realised through linguistic choices in Arabic by classical Muslim jurists to represent the difference between sex and gender, the use of their alternatives in English is appropriate when discussing the biological and social representation of individuals. The UK government refer to sex as “the biological aspects of an individual as determined by their anatomy … generally male or female something that is assigned at birth” and defines gender as “a social construction relating to behaviours and attributes based on labels of masculinity and femininity” [5]. A notable difference, however, between the Islamic perspective and modern definitions of gender is that the former views gender as ‘fitrah’ meaning natural, whereas the latter views it as a ‘social construct’.

The Holy Qur’an lists only two types of sexes and genders namely male and female; seemingly, centred on the notion that most people are cisgender and also because of its description of the genesis of humanity. The hadith literature, however, helps to understand that parents, as well as society at large, might on the rare occasion, assign the wrong gender to an individual at birth assumed from the biological features of a newborn. The fuqaha, therefore, have always been mindful of such erroneous gender assignments. For the social purpose of establishing civil laws, assigning sex to a newborn is necessary.

However, there has always been wide recognition in Shariah law of the fact that on rare occasions (yet not unknown), assigning sex is not a simple matter. Such matters are discussed in the sub-fiqh category known as nawazil, which addresses novel and contemporary issues. Statistically, 1 in 12,500 persons is born with such conditions [6]. As such, temporary gender would be assigned at birth but signs of sexual development would need to be monitored until even after puberty for the person to be able to identify their gender.During this interim period, linguists, physicians and the fuqaha referred to persons with such biological variations by the socially constructed category of ‘khuntha’ [7],which in modern terminology is best understood as ‘intersex’.

The Arabic construct is derived from the infinitive ‘khanth’ which is used to describe the act of turning the mouth of a water skin inside-out or vice versa realised as in the sentence ‘khanatha fam al-siqa’ [8]. The nominalisation of this verb to refer to an intersex person euphemistically is understood metaphorically by the fact that a person appears to be or senses internal conflict about their gender and sex. The NHS describes the “sense of unease that a person may have because of a mismatch between their biological sex and their gender identity” to define gender dysphoria (GD). An alternative Arabic etymological explanation of the construct is that it derives from the same root letters to mean ‘softness, gentleness, and tenderness’, which are characteristics to typically describe the softness of the voice of an intersex person [9]. An important distinction to make is that shu’ur is a strong natural feeling of ‘being’ and is dissimilar to a mere wish or a desire of ‘wanting to be’ (tamanna). GD is established by shu’ur and not tamanna. For example, shu’ur in children could be manifested through severe anxiety, depression, and signs of withdrawal whereas tamanna could be expressed through role-playing. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of GD is to be determined by expert gender psychologists. The media has played a role in portraying the notion that an average of 50 children a week are ‘referred to’ or that they ‘visit’ gender identity clinics in the UK. However, gender psychologists have ‘diagnosed’ a much smaller number. Moreover, around 75% of children with GD are likely to overcome it after puberty [10].

Importantly, a khuntha must not be confused with a ‘mukhannath’, ‘mutarajjila’, or a ‘khasees’. Mukhannath refers to a cismale, who does not identify as a female but deliberately dresses as one only for different personal and social reasons [9]. Likewise, a female who does not identify as male but like the mukhannath actively resembles males in clothing and speech is described in Arabic as a ‘mutarajjila’ [11][12]. Alternatively, a ‘mukhannath’ and a ‘mutarajjila’ are also described as ‘mutashabbiheen’ i.e. not naturally belonging to the gender but imitating the opposite gender.A castrated male is referred to as a ‘khasees’ [13][14].A khuntha, to clarify, is a person who explicitly self-identifies with a different gender than labelled at birth and not someone who merely wishes that they were born a different gender. Sheikh Rashid al-Olaimi of Kuwait stated that ‘to taunt persons with gender dysphoria as people imitating another gender is a serious sin that could warrant the displeasure of Allah; because the intersex person did not frivolously bring such matters on themselves; rather it was decreed by Allah in His wisdom’ [15].

Regarding the binary notion of gender in the Qur’an, al-Zamakhshari (d. 1144 CE) believed that the ‘haqiqa’ meaning the true gender of each individual is clear to Allah the All-Knowing. The Qur’an states that only Allah alone knows the true nature of that which develops inside the womb [16]. However, al-Zamakhshari adds that the determination of gender (tahdid al-jince) is ‘mushkil indana’ meaning we as humans are not always able to distinguish the gender of other human beings and sometimes, a person their own gender [17]. Al-Sarakhsi (d. 1090) also observed that sometimes a person appears to be neither male nor female (androgynous, non-binary) [18]. Alternatively, Imam al-Qurtubi proposed that only males and females are specified in the Qur’an because all are aware of this binary model, whereas the mention of khuntha might have led those who never came across their existence to consider the Qur’an to be mythical. Following this commentary, al-Qurtubi mentioned one of his intersex colleagues from Rabat who was known by the patronym of Abu Saeed. This person had no beard, had women-like breasts, and even had a maid. Al-Qurtubi confessed regretting never having asked the person about their gender out of shyness but wished he had [19]. Ibn Abi Hatim (d. 938), in his work on the biography of hadith narrators also mentioned an intersex teacher of Ahmad bin Uthman al-Awadi by the name of Hasan al-Talhi and described the narrator as having women-like breasts [20]. Al-Sakhawi (d. 1497) mentioned in the biography of al-Sharaf Musa bin Ahmad al-Subki, the famous 14th-century Shafi’i scholar that he never grew facial hair and that he was discovered to be intersex only during his funerary rites [21].

In any case, the sunnah of Muhammad Rasulullah (Peace be upon him, henceforth Rasulullah, PBUH) was that every person must be addressed and respected according to the way a person self-identifies; this could be realised in the English language through the use of their proper names, honorifications, and pronouns. On the other hand, using dated terms and slurs or making derogatory, pejorative, or stigmatising statements about intersex persons is forbidden in Shariah law and would be considered a violation of huquq al-ibad i.e. the rights of God’s creation because of the negative connotations words can carry and the impact they have on intersex persons and their families [22][23][24].

Classical Muslim jurists are praised by Risper-Chaim for seeking “innovative ways” to allow intersex persons to “participate in the community” [25]. El Fadl pointed out that in the Qur’an, the existence of diversity is to be viewed as a “primary purpose of creation” but has “remained underdeveloped in Islamic theology” [26].

Assigning sex to a newborn

From an Islamic jurisprudential perspective, a newborn needs to be assigned sex immediately primarily for inheritance purposes should the newborn or an individual in the family die unexpectedly. Sex also needs to be assigned for naming, upbringing, clothing, and socialisation purposes. However, the gender of an intersex newborn would remain unknown until the child identified their gender by ‘iqrar’. In most cases, parents or guardians hope that they have assigned the correct sex and that their child’s gender identity would be congruent with their body image. Importantly, Shariah law recognises that gender is clearer after puberty as a result of advanced sexual development. Assigning sex and identifying gender as a two-step process was also pointed out by classical Muslim jurists and recorded linguistically in their works as a) assigning sex to a ‘mawlood’ meaning a newborn as the first step and b) reviewing sex and gender ‘idha balagh’ meaning when the intersex person reaches puberty. Hasan Ibn Ali was once asked about a person whose gender could not be determined, he advised to defer the matter until puberty to see further signs of sexual development including menstruation [27].

- Assigning sex to a newborn

Traditionally in most cases, sex was assigned simply by observing the external genitalia of the baby. If the newborn had a penis, the sex assigned was male and if a vulva, then female. A person whose internal sense of gender corresponds with the sex the person had or was perceived as having at birth is described as cisgender. Chromosomal combinations were not possible for consideration and even if they are considered today, a baby born with an XY combination could still have female genitalia. Considering chromosomal combinations or hormones to assign a sex or gender remains a matter of debate in Shariah law [28]. Al-Jammas reported that “at least 50 “full men” were discovered until 1993 whose chromosomal structure was XX” [29].

In complex intersex cases, a newborn could have both male and female genitalia. Muslim physicians and fuqaha would categorise such intersex newborns as ‘khuntha wadhih’ translated in modern terms as ‘clearly intersex’. An inheritance case of one such intersex ‘mawlood’ was presented to Ali Ibn Abi Talib who was highly praised by Rasulullah (PBUH) for acting with resolve [30]. Ali advised that if the baby’s urethra is located in the penis then the child is to be considered male and if in the vulva then female [31]. There is no further information about that child’s sexual development or gender identity after puberty. From this case, we can learn that one way to assign the sex of a child before puberty is through ‘experimental’ methods such as urodynamic testing [25].

More complex cases involve an intersex newborn with external male genitalia as well as internal female glands. For instance, with respect to a ‘true gonadal intersex’, the person has both ovarian and testicular tissue. Other possibilities involve having them in the same gonad (ovotestis) or a person might have one ovary and one testis. Another possibility is to have external genitalia of males and females. With respect to 46, XY intersex individuals, the person has the XY chromosomes but the external genitalia are incompletely formed, ambiguous, or female whereas internally, the testes might be normal, malformed, or absent. By contrast, with respect to 46, XX intersex, the person has the XX chromosomes and ovaries, a uterus and fallopian tubes but has the external genitalia appear to be like those of males. In such cases, the labia are likely to be fused and the clitoris is enlarged making it form like a penis; most often caused when the female fetus has had exposure to excess male hormones before birth [32]. In fiqh terms, a true gonadal intersex,46, XY intersex, and 46, XX intersex can be categorised as ‘khuntha mushkil’ meaning an intersex person whose gender is indistinguishable. For further details on the pathophysiology of disorders of sexual development, read Mehmood and Rentea [33].

Monitoring of gender from age seven until puberty

During this period, monitoring gender identity and sexual development are crucial for social and religious reasons. Intersex children are encouraged, like all children, to perform salah and attend the masajid from the age of seven onward. Requirements for participating in worship differ for males and females. Perhaps, this sunnah is beneficial because it offers intersex children exposure to society and social gatherings to be able to establish their own gender identity by way of ‘iqrar’ developed from their actions, mannerisms, and inclinations. On this note, West and Zimmerman, state that “a person’s gender is not simply an aspect of what one is, but, more fundamentally, it is something that one does, and does recurrently, in interaction with others” [34]. Al-Isnawi (d. 1370) argued that gender can be revealed through interaction by conforming to behaviours and demonstrating attributes typical of males and females. A study by Cedars-Senai Medical Centre found that more than 70% of patients who experienced gender dysphoria were around age seven [35].

Affirmation of gender after puberty

The gender of a person after puberty is clearer and during this phase, the true gender of the person can be identified. For hajj and umrah purposes, affirming gender at this stage is significant because of the laws related to ihram. Indicators of gender can be categorised into major and minor sexual developments.

Major developments include getting pregnant or giving birth; both of which, according to Hasmady and Shamsuddin unequivocally establish a person as a female in Shariah law [36]. For inheritance purposes, a person who gives birth is given the status of ‘mother’. The reason given for this assignment is that the Qur’an associates pregnancy [37][38] and delivery [39] with ‘motherhood’. Likewise, Hasmady and Shamsuddin argue that the ability to impregnate a woman unequivocally establishes a person as malein Shariah law and at birth, he will have the status of ‘father’. Sexual orientation (maylan) is another indicator of gender identity if the intersex person identifies as heterosexual [40]. Correspondingly, inclination toward males could help the intersex person establish their identity as female, conversely, inclination toward females could help the person establish their identity as male. In relation to the first ever gender correction surgery case in the Emirates, Consultant Pediatric Surgeon Dr Amin El-Gohary asserts that there exists ‘great confusion between the concept of gender identity and homosexuality’ i.e. they are fundamentally two separate concepts: gender identity is related to a person’s belief about their own gender [15].

Another legal case presented to Ali Ibn Abi Talib involved an intersex person who had both male and female genitalia and was identified as a male despite society perceiving this person as female [41]. This person and their husband had a maid who when she gave birth, both persons claimed the child. Among the factors that Ali considered was the fact that this person was sexually attracted to women and even impregnated one. Interestingly, when inspection of the genitalia of the intersex person was necessary, Ali would respectfully take two important measures a) that only a khasee was authorised to do so, perhaps due to the absence of other intersex persons and b) that the inspection was carried out via a mirror reflection.

Minor developments that could help one to identify their gender include beard or chest hair growth for males and growth of breasts for females. Hair type and vocal attributes could also help to realise gender among other anatomical features of the body. As for menstruation, al-Isnawi suggested that only if it occurs more than three times and is regular can it be considered a female characteristic [42].

As for exactly who decides on the gender is a matter that needs further discussion. In the above-mentioned cases such as the Ansari newborn and the intersex person who identified as male, different people were involved in the assignment process for different reasons. In the Ansari case, the baby can be considered too young to have established a gender identity and Ali’s assistance was sought. In the second case, the intersex person was married to a male and had impregnated their maid. A dispute arose as to who the father of the child was i.e. was it the intersex person or the husband? As this case had become a legal matter, Ali’s involvement was required. However, aside from such court cases, al-Kharaqi (d. 946 CE) asserted that if an intersex person self-identifies as male then the person is male and if as female then female. Al-Zarkashi (d.1392 CE) supported al-Kharaqi’s approach adding that the intersex person is the only person who can reveal their gender and their gender identity must be respected and accepted just as when a female states that she is menstruating [43]. Al-Sarakhsi (d.1090) also reiterated the point that in all internal psychological and biological matters, the word of the person – to whom the matter applies – is ‘shar’an maqbool’ meaning valid in Shariah law [44].

Some Shia scholars, proferred another category whereby they classified some intersex persons as having ‘al-tabi’a al-thalitha’ literally meaning the third gender [45][46][47][48]. Zain al-Din al-Juba’I al-Amili (d. 1558) argued that there is no evidence in the Qur’an that a third gender could not exist [49]. Alternatively, Al-Haydari [50] concedes that intersex persons, especially those whose gender is indistinguishable, are beyond our social constructs in light of the verse ‘and He (Allah) creates that which is unknown to you’ [51]. Accordingly, and in light of al-Zamakhshari’s view, intersex persons pose a challenge to society only because society struggles to situate them according to its constructs.

In spite of the gender spectrum, fiqh rulings are predicated on a binary model which implies that Sharia law has no exclusive jurisprudential model for intersex persons, although flexibility is provided. The fuqaha, therefore, advised that intersex persons choose either fiqh whilst maintaining their gender identity. On that note, the fiqh depends on the gender of the person and not vice versa. In hajj, for example, males are to uncover their heads and avoid wearing knitted clothes. Females, on the other hand, cover their hair and can wear knitted clothes. Now, simply because these rulings are predicated on a gender-binary model does not necessitate that every individual neatly fits into the binary gender model.

Moreover, simply because one chooses to uncover their hair does not make a person male. Rather, the fiqh follows gender and so if a person identifies as male then they are required to uncover the head and if as female, then to cover. If intersex, then as Ibn Qudama (d. 1223) suggests, the matter remains flexible as long as the rulings do not conflict. For example, an intersex person could choose either option but is advised to avoid an approach that would result in what would be a violation of rules for both genders simultaneously; for instance, if an intersex person wore knitted clothes but at the same time exposed their hair [52]. Another such scenario applies to wearing gold and silk, which are permitted for females but not males. Al-Sarakhsi recommended that perhaps, the best choice for an intersex gender-seeking person is to avoid wearing them to conform to the hadith ‘leave that which causes doubt for that which does not cause doubt’ [44].

For children, the rationale for prescribing puberty blockers is to ‘pause’ and ‘buy time’ to make decisions. However, the treatment has been considered experimental with unknown long-term effects. Puberty blockers are said to rewire neural circuits and affect brain maturity and neurocognitive development, temporarily or permanently, which could disrupt the decision-making process and consequently, have the opposite effect to the one claimed [53].

Two main types of gender-related surgeries

Another aspect related to intersex persons involves examining the case of individuals who have established their gender and have self-identified as either male or female. If an intersex person is satisfied with their physical characteristics then they need not be pressured into any form of treatment that would alter these characteristics. Intersex persons need not necessarily conform to standards of beauty for males and females but embrace beauty as viewed by intersex persons. Malim and Padela highlight that:

It may be appropriate for an individual to carry on in life without fitting into a gender binary as male or female, and society should accommodate for this gender ambiguous position as something that is normal, even if not very commonly seen, as discussed in Kitab al Khuntha. This idea may not be easily fit into all societies, including Muslim ones where a strict gender binary is deemed normative, but nonetheless Islamic texts presuppose the notion [3].

If on the other hand, the intersex person wishes to undergo ‘corrective surgery’ then again there are further considerations for the patient, physicians, and the fuqaha. A salient point to distinguish is that when a cisgender person wishes to change their sex or gender then the procedure is known as ‘sex reassignment surgery’ (SRS) and in Arabic ‘tahweel al-jince’. When an intersex person, on the other hand, wishes to undergo surgery to ‘affirm’ their sex and gender; this type of surgery is known as gender-affirming surgery, gender-affirmation surgery, and gender-confirming surgery (GCS) and in Arabic ‘tas’heeh al-jince’ or ‘tathbeet al-jince’ [54]. Muslim jurists Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (d. 1449) and al-Qastalani (d. 1517) both encouraged intersex persons to seek gender-correcting treatment [55].

Muslim jurists agree that GAS is permitted only after gender has been determined as either male or female otherwise the procedure would be futile and the genitalia of the patient would be manipulated without justification [2].

Tas’heeh al-jince is not to be conflated with the concept of ‘taghyeer khalq Allah’ meaning ‘altering the creation of Allah’. The reason for referring to the surgery as ‘tas’heeh’ and not ‘taghyeer’ is because the person’s true gender does not change but is realised and affirmed. Perhaps, the most controversial case in modern times was that of a male in Egypt by the name of ‘Sayyid Abd Allah’ who was described by two independent gender psychologists as a ‘khuntha al-nafsiyya’ meaning psychologically intersex. Sayyad underwent surgery and adopted her new name ‘Sally’ [55][56].

A difference of opinion remains on whether this procedure was a sex ‘change’ or ‘affirmation’.

Tas’heeh al-jince

Physical characteristics and features that are socially considered desirable in terms of aesthetics and function exclusively in males include the penis along with the glans or the tip, scrotum and testicles, beard and chest hair. By contrast, characteristics and features that are socially considered desirable exclusively in females include a vagina, breasts, uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and menstruation. Such desirable features for males and females can be termed ‘al-udw al-asli al-sahih’ which can be loosely translated as ‘correct features’. Conversely, the same physical characteristics and features that are socially considered desirable exclusively for males are typically by contrast, undesirable for females and vice versa. Consequently, these undesired features can be termed ‘al-udw bi-manzilat al-ayb’ which can be loosely translated as ‘conflicting features’.

The questions or the dilemma that arise for intersex patients, physicians, and the fuqaha include a) if the correct features have defects in any way, shape, or form then from an Islamic perspective, can they be ‘surgically corrected’? and b) from an Islamic perspective, can conflicting features be surgically modified? The answer to these questions has implications for a range of surgical procedures including but not limited to:

- Correcting male features: metoidioplasty or phalloplasty, erectile implants, glans penis correction, growing beard and chest hair, scrotoplasty, sperm fertility, testicular implants, urethral lengthening

- Correcting female features: vaginoplasty, breasts augmentation, clitoroplasty, facial Feminisation, feminising genitoplasty, labiaplasty

- Correcting conflicting features in males: vaginectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), chest reconstruction, gynaecomastia, hysterectomy, mastectomy

- Correcting conflicting features in females: vasectomy, chondrolaryngoplasty, gonadectomy, orchiectomy, penectomy, tracheal shave

Fatawa in favour of tas’heeh al-jince

Two major medical cases in recent decades related to intersex persons led to two impactful fatwas from two prominent jurists of their time. The first case was in Iran, in which Fereydoon Mulkara, who was socially perceived as a male, later identified as Maryam Khatoon Mulkara (1950-2012) [57][58][59]. The second case was in Egypt, where Sayyad Abd Allah, another socially perceived male, underwent surgery which became an ethico-legal matter in court. The first case was approved via a fatwa by Ruhullah Khomeini which appears to have also influenced the outcome of the second case approved by the then Grand Mufti of Egypt, Sayyad al-Tantawi [55][56].

Khomeini issued two fatwas related to sex-reassignment surgery. The first was in 1964, wherein he stated that for an intersex person, although permitted, gender affirmation surgery was not obligatory. Maryam, during this period, whilst still having male genitalia wore women’s clothing and was permitted to marry and even married twice. After the 1979 revolution, Maryam faced persecution and was ‘harassed, even jailed and tortured’ [60]. In 1981, the Malaysian Center for Islamic Research reached out to the then Grand Mufti of al-Azhar, Jadd al-Haqq Ali Jadd al-Haqq regarding sex-change operations [61]. His fatwa not only permitted the surgery but also encouraged it provided that it would have a high probability of success. Returning to Maryam’s case in Iran, she eventually met with Khomeini in person circa 1987 to discuss her situation. Khomeini consulted three of his trusted doctors to review the case and concluded that surgery was a valid option from an Islamic perspective. In his revised fatwa, Khomeini recommended that reliable medical doctors must be consulted when considering reassignment surgery. Alipour presumes that the reason for the consultation was that the surgery would be irreversible with lifelong consequences [56]. Maryam underwent the surgical operation in 1997 and then established Himayat az bimaran-i mub-tala bah ikhtilal-i huviyat-i jinsi Iran (the Iranian Society to Support Individuals with Gender Identity Disorder, ISIGID)in 2007.

A year after Khomeini’s fatwa, in 1988, Sayyad al-Tantawi was faced with the case of Sayyad Abd Allah, a student at al-Azhar. In his fatwa, al-Tantawi reiterated Jadd al-Haqq’s fatwa but with additional points. Al-Tantawi acknowledged that some persons might not show any physical signs of intersex (khuntha khalqi), however, they might still strongly sense that their body is not congruent with their body image (Khuntha nafsiyya). Like Khomeini, al-Tantawi left the matter with expert physicians to investigate two types of conditions a) matmura, where a female’s nature is concealed and b) maghmura, where a male’s nature is concealed. Al-Tantawi’s metaphor thereby advocated for ‘uncovering’ one’s true gender.

Implications of the fatwas

The reaction of two influential jurists to the cases of Maryam and Sally has since sparked interest and discussion among medical experts and the fuqaha. With regard to the nature of tas’heeh al-jince, the Islamic Fiqh Council of the Muslim World League concluded in their resolution at Mecca in 1989 that the surgery is permitted and should be understood that the purpose is clinical to reveal the true condition of the person and not ‘taghyeer khalq Allah’ meaning to tamper with the creation of Allah [62].

The Permanent Scientific Committee for Research and Ifta (Al-Lajna al-Da’ima lilBuhuth al-‘Ilmiyya wal-Ifta) in Saudi reiterated the same fatwa in 1990 [63]. The opinion of the General Secretariat of the Council of Senior Scholars, specified in their 39th session held at Ta’if that treatment is permitted by hormone therapy as well as surgery [64]. Another fatwa from Egypt stated the legality of performing gonadectomies or hysterectomies for intersex persons [65]. In 2006, the Fatwa Committee National Council of Islamic Religious Affairs Malaysia also permitted the surgery adding that gonadectomy to prevent malignancy is also permitted [65]. A point on fertility matters was also added wherein the fatwa stated that the egg or sperm must come from the intersex person themselves [67].

In terms of the impact of the fatwas on medical practice, GAS has increased in Iran and Saudi Arabia. In 2015, Dr Mirjalali, Iran’s leading surgeon, stated that whereas “In Europe, a surgeon would do about 40 sex change operations in a decade”, he had conducted 320 over a period of 12 years in Iran [68]. Similarly, Prof. Yasir Salih Jamal highlighted the value of the fatwas stating that GAS is carried out in the university hospital according to the fatwas of religious references in Saudi Arabia [69]. He also added that he had witnessed over the last two decades, a major shift in treatment, diagnostically and therapeutically, with the advancement of genetic hormonal analysis and types of medical imaging, sonogram, tomography, magnetic, endoscopy, and diagnostic tissue study. Like Mirjalali, Jamal pointed out that he too over a period of 25 years had conducted more than 300 operations for males and females.

The most striking experience for Jamal was performing GAS on five sisters ranging between the ages of 38 and 17, who now live as five brothers. Another case that Jamal described as memorable was an intersex person by the name of Fatima who came for hajj, underwent surgery and returned as Muhammad. 15 years later, this person also had an intersex child, and because of early diagnosis after birth, the surgery was better than the father’s.

In 2017, Pakistan’s census recorded approximately 100,000 transgender people. To accommodate those who identify as Muslims, Pakistan saw its first madrasa to integrate intersex Muslims [70]. Likewise, through a private initiative, the first madrasa for intersex Muslims was opened in Dhaka, Bangladesh [71]. In 2008, after the Indonesia earthquake, which had a magnitude of 6.3 and which caused 4,000 deaths, a madrasa was founded for intersex persons. The director of the madrasa, Shintra Ratri stated that “It was a time of suffering … and we needed a place to worship together and learn about Islam” [72].

Returning to the resolve of Ali ibn Abi Talib, he not only legally established and accepted the gender of the person but went a step further and celebrated the notion by establishing a gesture as a rite of passage. After Ali concluded the case that the person was to be respected as a male, he offered the person male clothing. In Maryam’s case, we see the same gesture when the then president and second Supreme Leader after Khomeini at the time, Khamenei, gifted her with a chador. Moreover, Maryam was provided with a new birth certificate, a new identity card, a new passport, and even a loan from the government. Likewise, Prof. Jamal described that the five brothers were given 30,000 Saudi Riyals as a donation from the royal family plus two years’ worth of rent covered financially.

Ethical considerations

Having discussed the views and opinions of Muslim jurists, the final decision of undertaking GAS lies with the intersex person. Because the outcome would be irreversible with lifelong consequences, the decision must be wellinformed. Rasulullah (PBUH) advised that a person who seeks a positive outcome from Allah (istikhara) and heeds the advice of others (mashwara) is less likely to regret their decision. He also strongly advised that those whose advice is consulted are accountable to Allah if misleading or misinformed advice is given. On that note, faith leaders need to understand the science related to gender, be up to date with the latest terms and developments in gender studies and surgery as well as be aware of the benefits and risks. In the context of GAS, an intersex person is advised to consult loved ones, the fuqaha, and medical experts inclusive of gender psychologists. Should a representative from these groups be absent, all effort must be spent to invite them as each group has a vital role to play and to make the decision-making process holistic.

Firstly, only the intersex person can truly reveal their gender whilst others can only assist them to realise what that gender is. The intersex person must be aware that choosing surgery is only an option and not obligatory according to Shariah law. No pressure, therefore, must be felt to undergo any surgery. Any decisions being made related to treatment need to be weighed considering the emotional and mental vulnerability of the intersex person. As per the advice of classical fuqaha, an intersex person who is gender questioning should be allowed exposure to both genders so that the decision is based on shu’ur that would be developed from lived experience among both genders and to avoid shock or trauma post-surgery. The intersex person must also be aware of the social norms, customs, and traditions in their milieux, which are in most cases, rooted in the gender binary model. At birth, only sex is assigned to the newborn, however, gender can only be truly realised as the child begins to form an identity that is realised through behaviour, a strong sense of gender, and sexual development. During the Khilafah period, we find the existence of intersex persons who were embraced.

As seen in the cases of Maryam and Sally, gender psychologists have a key role to play in assisting intersex persons to realise their true gender. The role also includes post-surgical psychological care to help individuals adapt to their gender roles. As with any medical treatment, Shariah law encourages avoiding any medication in the first instance and encourages patients to allow nature to take its course. Concerning gender, intersex persons should not have to feel obliged to undertake surgery because they are facing discrimination from family members or the wider society. Should this be the case, then the fuqaha are responsible for addressing such vices (nahy an al-munkar) and for reiterating the rights of people (huquq al-ibad). Accordingly, gender marginalisation, subordination, stereotyping, and violence against men, women, and intersex persons are all forms of social illnesses that the fuqaha need to address. Moreover, the Qur’an reprimands people who refuse to ‘accept the glad tiding of learning that a person is female’ [73]. On that note, an intersex person who identifies as female should not be discouraged to identify as such by others simply because of sexist attitudes toward females. Society needs to accept that such persons were erroneously assigned male at birth (AMAB). Moreover, society should celebrate and embrace the moment an intersex person has realised their gender identity as an occasion of ‘glad tiding’.

An additional role of the fuqaha involves reminding the intersex person of the different rulings related to ritual purity and worship according to gender and the possible reaction of the intersex person’s society according to the way the madhab is socially practised; in terms of effects on an existing marriage if applicable, accommodation in the masajid, travelling with or without a mahram, especially for hajj and umrah purposes, education provisions if segregation is practised, inheritance portions, and offering and being given funerary rites [74]. The fuqaha must also allow the time and space for an intersex person to come to an informed decision but may encourage the person to be mindful of Islamic rulings. The fuqaha are also reminded that Rasulullah (PBUH) stated that a true believer must always be mindful of the welfare of the entire ummah. Irrespective of gender, the fuqaha must echo Qur’anic values which state that all are created equal and by piety alone, one reaches greatness.

If the decision to undergo any correction is a personal choice without any such external social pressure then again, as per Shariah law, the advice would be to take the least invasive options such as hormone therapy. Lastly, if the only option is irreversible invasive surgery, then medical experts need to be very clear about expectations in terms of unguaranteed true sex assignment, physical and psychological health risks [75], the source of skin and tissue for reconstructive surgery, function, sensation, aesthetics, fertility, and recovery. Meyer-Bahlburg also asserts that “The clinician’s role is not to superimpose her/his cultural values on those of others, but to come to a decision that likely minimizes potential harm to the patient in his/her cultural environment” [76]. From a fiqh perspective, consent would only be valid if the intersex person has sufficient maturity and capacity to comprehend the consequences of the treatment. Moreover, the consent needs to be well-informed and explicit.

Conclusion

The notion of khuntha is a social construct by classical fuqaha to allow intersex persons to engage and contribute to society and was never intended to marginalise them as being beyond the strict gender binary model. Assignment of sex has traditionally been attested by experimental testing which involves identifying the genitalia of the newborn. Modern approaches can assist sex assignment at chromosomal, gonadal, reproductive, and behavioural levels. The flexible nature of the Sharia legal framework also allows corrections in case of error. Gender, on the other hand, is realised after puberty once a person develops and matures sexually, physically, and psychologically. Muslim jurists have also recognised that orientation does not necessarily match one’s sex organs. Tas’heeh al-jince, also known as GAS, is considered to be a ‘corrective’ surgery by key Muslim jurists and organisations. Because the treatment is irreversible with lifelong consequences, several ethical issues must be considered collectively by a panel which needs to include the intersex person, their loved ones, gender psychologists, surgeons, and the fuqaha.

Further research is required from an Islamic perspective on the journey of British intersex Muslims and the thoughtprocess of parents. Further research is also necessary concerning the impact of puberty blockers as a safe and viable long-term option for children especially those that present neurodiversity. The intersex fiqh network is proposed to encourage interdisciplinary dialogue between health care professionals and the fuqaha using terms that require familiarisation from both groups.Furthermore, the fuqaha need to revisit the fiqh of intersex Muslims and monitor the social treatment of intersex persons in society and help to create an environment wherein an intersex person is respected as a human being and as a creation of Allah the Most Merciful. Lastly, more statistical information needs to be shared with faith leaders concerning the actual number of GD referrals, confirmed cases, number of referrals for hormone therapy and GAS, and outcomes to help curb fears and avoid exaggerated claims about its commonality.

Table 1. Intersex fiqh network

References

[1] Sax, L. How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling. Journal of Sex Research. 2002, 39(3), 174-8.

[2] Zabidi, T. Analytical review of contemporary fatwas in resolving biomedical issues over gender ambiguity. Journal of Religion and Health, 2019, 58(1), 153-167.

[3] Malim, N. and Padela, A.I. Islamic Bioethical Perspectives on Gender Identity for Intersex Patients. JBIMA, 2020, 5(2), 19-27.

[4] Al-Shaybani, M.H. Al-Asal; Kitab al-khuntha (vol. 3). Beirut, Lebanon: Dar Ibn Hazm; 2012.

[5] UK Library. International non-binary people’s day; sex, gender, and identity [Internet]; 2021 July 14 [cited 2022, Jul 5]. Available from: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/international-non-binary-peoples-day

[6] Dreger, A.D. Hermaphrodites and the medical invention of sex. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

[7] Ibn Manzur, M.M. Lisan al-arab. Kuwait: Dar al-Nawadir; 2010.

[8] Lane, E.W. An Arabic-English Lexicon; خنث. London: Williams and Norgate; 1872.

[9] Rowson, E. K. The effeminates of early medina. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 1991, 111(4), 671-693.

[10] Lee, G. FactCheck Q&A: How many children are going to gender identity clinics in the UK? [Internet]; 2017, Oct 24 [cited 2022, Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.channel4.com/news/factcheck/factcheck-qa-how-many-children-are-going-to-gender-identity-clinics-in-the-uk

[11] Kugle, S.S. Homosexuality in Islam: Critical reflection on gay, lesbian, and transgender Muslims. Oxford, UK: Oneworld; 2012

[12] Bouhdiba, A. Sexuality in Islam, Translated by: Alan Sheridan. London, UK: Saqi Books; 2012.

[13] Marmon, S. Eunuchs and sacred boundaries in Islamic society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1995.

[14] Nolen, J. L. Eunuch. In Encyclopedia Britannica[Internet]; 2009 [cited 2022, Jul 5]. Available from: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/195333/eunuch

[15] Alittihad. Jadal hawla awwal qadhiyya tas’heeh jince bi’d dawla [Internet]; 2016, Sep 26 [cited 2022, Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.alittihad.ae/article/46398/2016/ جدل-حول-أول-قضية-تصحيح-جنس-بالدولةجدل-حول-أول-قضية-تصحيح-جنس-بالدولة

[16] The Holy Qur’an: chapter 31, verse 34.

[17] Al-Zamakhshari, M.U. Al-Kashaaf an haqa’iq ghawamidh al-tanzil; 92:3. Beirut, Lebanon; Dar al-Kitab al-Arabi; 1986.

[18] Sanders, P. Gendering the Ungendered Body: Hermaphrodites in Medieval Islamic Law. In: Beth B. and Nikki K. (eds.). Women in Middle Eastern History: Shifting Boundaries in Sex and Gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1991. p.74-95.

[19] Al-Qurtubi. Al-Jami li-ahkam al-Qur’an; 42:51. Cairo, Egypt: Dar al-Kutub al-Masriyya; 1964.

[20] Ibn Abi Hatim, A. Al-jarh wa’t ta’deel; Bab al-Ha’: Al-Hasan. Beirut, Lebanon: Dar Ihya al-turath al-Arabi; 1952.

[21] Al-Sakhawi, M. Adh-dhaw’ al-lami’ li’ahl al-qarn at-tasi’ (vol. 10). Beirut, Lebanon: Makatabat al-Hayat’; 1991.

[22] Reis, E. Divergence or disorder?: The politics of naming intersex. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2007, 50(4), 535-543.

[23] Aaronson, I.A. and Aaronson, A.J. How should we classify intersex disorders? Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2010, 6(5), 433-436.

[24] Hughes, I.A. Disorder of sex development: A new definition and classification. Best Practice and Research Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008, 22(1), 119-134.

[25] Rispler-Chaim, V. Disability in Islamic Law. Springer; 2006.

[26] El Fadl, K. The place of tolerance in Islam. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2002.

[27] Al-Utaridi, A. Musnad al-Imam al-Mujtaba Abi Muhammad al-Hasan bin Ali alayhim as-salam. N.D.

[28] Al-Hajiri, H.M. Hukm tahdeed jince al-janeen [pdf]; 2021, Jun 2 [cited 2022, Jul 17]. Available from: https://hamadalhajri.net/files/books/حكم تحديد جنس الجنين.pdf

[29] Al-Jammas, D. Dirasat Tibbiyya Fiqhiyya Mu’asira. Damascus: Markaz Nur al-Sha’m lilKitab; 1993.

[30] Al-Sakhawi, M. Al-Maqasid al-hasana fi bayan katheer min al-hadith al-mushtahira ala’l alsina; hadith ‘wa aqdhakum Ali’. Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Kitab al-Arabi; 1985.

[31] Bayhaqi, A. Sunan al-Kubra; Kitab al-fara’idh, Jumma’u Abwab al-Jadd, Bab mirath al-khuntha. Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah; 2003.

[32] Medline Plus. Intersex [Internet]; N.D. [cited 2022, Jul 9]. Availablefrom: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001669.htm

[33] Mehmood, K.T. and Rentea, R.M. Ambiguous Genitalia And Disorders of Sexual Differentiation. StatPearls [Internet]; 2022, May 8 [cited 2022, May 8]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557435/

[34] West, C. and Zimmerman, D.H. Doing gender. Gender & society. 1987; 1(2): 125-51.

[35] Zaliznyak, M.Bresee, C. and Garcia, M.M. Age at First Experience of Gender Dysphoria Among Transgender Adults Seeking Gender-Affirming Surgery. JAMA Network Open, 2020, 3(3), e201236.

[36] Hasmady, F. and Shamsuddin, M.Hukm tahweel al-jince: dirasa taqweemiyya fi dhaw’ masqasid al-shari’a. Malaysia, IIUM Press; 2018.

[37] The Holy Qur’an: chapter 13, verse 8.

[38] The Holy Qur’an: chapter 35, verse 11.

[39] The Holy Qur’an: chapter 58, verse 2.

[40] Wazarat al-awqaf wash-u’un al-Islamiyya. Al-Mawsouat al-fiqhiyya al-Kuwaitiyya (vol 20). Kuwait: Dar al-Salasil; 2006.

[41] Al-Sadouq, M. Man la yahdhuruhu’l faqeeh. Bab mirath al-khuntha. Qom, Iran: Mu’assasat al-nashr al-Islami al-tabi’a li-jama’at al-mudarriseen bi-qum al-muqaddasa; 1992.

[42] Al-Isnawi, A. Eidha al-mushkil min ahkam al-khuntha al-mushkil. Kuwait: Asfaar; 2021.

[43] Al-Zarkashi, M. Sharh al-Zarkashi ala mukhtasar al-Kharaqi (vol. 5). Al-Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Maktabat al-Obaikan;

[44] Al-Sarakhsi, A. M. Al-Mabsut. Kitab al-Khuntha. Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyyah; 1997.

[45] Al-Hilli, H.Y. Mukhtalaf al-Shi’a Fi Ahkam al-Shari’a. Qom, Iran: Intisharat-I Islami; 1993.

[46] Al-Yazdi, M.K. Hashiya al-Makasib (vol 1). Qom, Iran: Intisharat-I Isma’iliyan; 2000.

[47] Al-Hilli, M.M. Al-Sara’ir. Qom, Iran: Intisharat-i Islami; 2006.

[48] Naraqi, A.M. Mustanad al-Shi’a. Qom, Iran: Mu’assasa Al al-Bait; 1994.

[49] Al-Amili, Z. Al-Ruda al-bahiya fi sharh al-lum‘a al-Damishqiya (al-Muhashsha- Sulṭan al-‘ulama). Qom, Iran: Intisharat-i Daftar-i Tabliqat-I Islami; 1992.

[50] Al-Haydari, S.K. Fiqh al-mar’a (125) – Kayfa khuliqat al-mar’a (7) [Internet]; 2018, Nov 24 [cited 2022, May 15]. Available from: http://alhaydari.com/ar/2018/11/66431/

[51] The Holy Qur’an: chapter 16, verse 8.

[52] Ibn Qudama, A.A. Al-Mughni. Kitab al-hajj; Bab ma yatawaqqa’l muhrim wa ubiha lah; mas’alat as-sunna fi’l mar’a an la tarfa’ sawtaha bi’t talbia; fasl idha ahram al-khuntha al-mushkil lam yalzimuhu ijtinab al-makheet. Cairo, Egypt: Maktaba al-Qahira; 1968.

[53] Kirkup, T. Why the Tavistock clinic had to be shut down [Internet]; 2022, 28 July [cited 2022, 28 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/why-the-tavistock-clinic-had-to-be-shut-down

[54] Al-Sharqawi, I. Tathbit al-jins wa atharuhu: dirasah muqaranah fi’l fiqh al-Islami wa’l qanun al-wadh’i. Cairo, Egypt: Dar al-Kutub al-Qanuniah; 2002.

[55] Skovgaard-Petersen, J. Sex Change in Cairo: Gender and Islamic Law. The Journal of the International Institute, 1995, 2(3).

[56] Alipour, M. Islamic shari’a law, neotraditionalist Muslim scholars and transgender sex-reassignment surgery: A case study of Ayatollah Khomeini’s and Sheikh al-Tantawi’s fatwas. International Journal of Transgenderism, 2017, 18(1), 91-103.

[57] Bloor, B. Sex-change operation in Iran [Internet]; 2006, May 19 [cited 2022, Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/arts/story/2006/05/060519_7thday_bs_transexual.shtml

[58] McDowall, A. and Stephen, K.The Ayatollah and the transsexual [Internet]; 2004, Nov 25 [cited 2022, Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/the-ayatollah-and-the-transsexual-21867.html

[59] Tait, R. A fatwa for freedom [Internet]; 2005, July 27 [cited 2022, Jul 14]. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/jul/27/gayrights.iran

[60] Fathi, N. As repression eases, more Iranians change their sex [Internet]; 2004, Aug 2 [cited 2022, Jul 17]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/02/world/as-repression-eases-more-iranians-change-their-sex.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

[61] Saqar, A. Fatawa Dar al-ifta al-Masriyya; Tahweel al-jince ila jince akhar [Internet]; 1994 April 15 [cited 2022, Jul 6]. Available from: http://islamport.com/w/ftw/Web/953/4478.htm

[62] Al-Salafi, A.J. Al-Muntada al-shar’i al-aam, 45, qarar majma’ al-fiqh al-Islami fi hukm amaliyyat tahweel al-jince (1989, session 11, resolution 6) [Internet]; N.D. [cited 2022, Jun 9]. Available from: https://al-maktaba.org/book/31621/23054

[63] Al-Lajna al-Da’ima lilBuhuth al-‘Ilmiyya wal-Ifta Fatwa #1542 [Internet]; 1990 [cited 2022, May 19].

[64] Majallat al-buhuth al-Islamiyya (vol. 49). Hukm tahweel al-dhakar ila untha wa’l untha ila dhakar; #176 [Internet]; 1413 AH, R.A 17 [cited 2022, Jul 15]. https://al-maktaba.org/book/34106/22178#p1

[65] Dessouky, N. Gender assignment for children with intersex problems: An Egyptian perspective. Egyptian Journal of Surgery. 2001, 20, 499-515.

[66] Zainuddin, A.A. and Mahdy, Z.A. The Islamic Perspectives of Gender-Related Issues in the Management of Patients With Disorders of Sex Development. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 2016, 46(2), 353-360.

[67] Ebrahim, A.F.M. An introduction to Islamic medical jurisprudence. Durban: The Islamic Medical Association of South Africa; 2008.

[68] Harisson, F. Iran’s sex-change operations [Internet]; 2005, Jan 5 [cited 2022, Jul 3]. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/newsnight/4115535.stm

[69] Jarousha, Y. Wali al-ahd yatabarra’ lir-rijal al-khamsa al-ashiqqa’ [Internet]; 2006, Sep 5 [cited 2022, Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.alriyadh.com/184263

[70] Shahzad, A. A transgender Islamic school in Pakistan breaks barriers [Internet]; 2021, Mar 22 [cited 2022, Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-pakistan-lgbt-madrasa-idUKKBN2BE038

[71] Benar News. An Islamic School for Transgender Students Opens in Bangladesh [YouTube]; 2020, Nov 12 [cited 2022, Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qNxnrGtixPw

[72] Emont, J. Transgender Muslims Find a Home for Prayer in Indonesia [Internet]; 2015, Dec 22 [cited 2022, Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/23/world/asia/indonesia-transgender-muslim.html

[73] The Holy Qur’an: chapter 16, verses 58-59

[74] Tak Z. Khuntha dan Mukhannath Menurut Perspektif Islam. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia; 1998.

[75] Al-Majlis al-Islami li’l Ifta. Tas’heeh jince al-khuntha bi-wasitat al-amaliyyat al-jarahiyya; #658 [Internet]; 2012, Nov 12 [cited 2022, Jul 7]. Available from: Retrieved from http://www.fatawah.net/Fatawah/658.aspx

[76] Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F.L. Gender and sexuality in classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Endocrinology Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2001,30(1), 155-171.